I’m sure you’ve heard the cue “Micro-bend your knee to protect your knee joint,” or something similar in a yoga class. Maybe you’ve used this cue many times yourself. It stems from the idea that hyperextending (often referred to as “locking”) the knee is inherently harmful. Below you’ll learn the anatomy of hyperextension and find out if doing so is problematic or not.

This topic is explored in detain in my book, Supporting Yoga Students with Common Injuries and Conditions:

One of the biggest misconceptions about the knee joint is that it is purely a hinge joint that only moves in one plane. The knee can actually be thought of as a gliding hinge joint that can roll, glide and rotate. The joint is able to move in three different planes and this offers a ‘six degrees of freedom’ range of motion, including the primary movements of flexion and extension in the sagittal plane, a small amount of internal and external rotation in the transverse plane and varus (lateral) and valgus (medial) stress in the frontal plane. Translational movement is possible in anterior–posterior and medial–lateral direction as well as by compression and distraction of the knee joint.

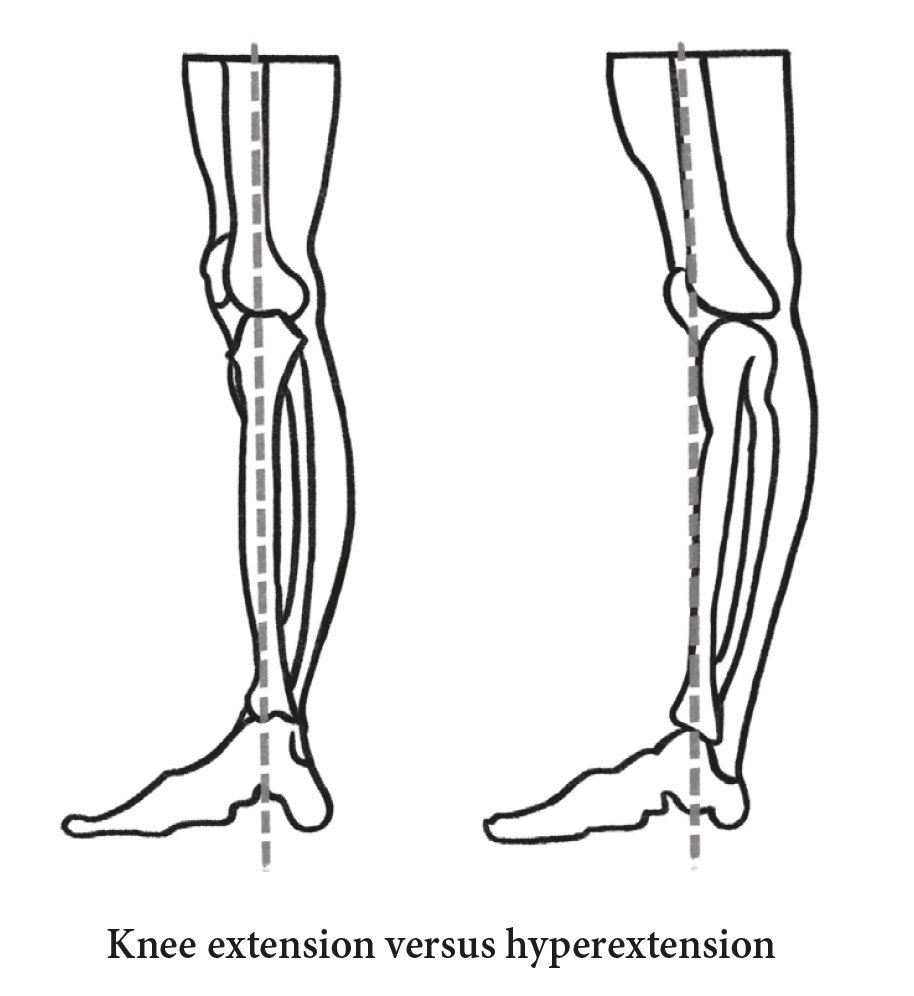

The terms hyperextension and locking of the knee joint each have different meanings depending on the context. In the medical world, knee hyperextension (or genu recurvatum) is a deformity in the knee joint where excessive extension occurs and the knee bends backwards. In terms of anatomical language hyperextension of the knee is simply extending the knee beyond 180°. In the fitness world the term ‘locking’ the knee is often used interchangeably with hyperextension. This phrase actually refers to the ‘screw-home’ mechanism involving lateral rotation that occurs at full extension of the knee to create stability.

There is very limited literature regarding hyperextension of the knee joint. Gray et al (2005) stated that overextension of the knee joint is prevented by the tension of the anterior cruciate, oblique popliteal, and collateral ligaments while Morgan et al (2010) shared that the oblique popliteal ligament specifically limits hyperextension of the knee. Loudon et al (1998) stated that during knee hyperextension the femur tilts forward relative to the tibia creating anterior compression between the femur and tibia. In this position, the posterior structures are placed in tension, which helps to stabilize the knee joint, and no quadriceps muscle activity is necessary. This can be seen in individuals following a cerebral vascular accident who lose motor control of the quadriceps and are still able to stand. Therefore, it can be concluded that in a standing position when the knee is hyperextended, we can bear weight using the strength of these knee ligaments and not the knee musculature.

In an ideal scenario, hyperextension of the knee should be a choice that we are making and not just the default knee position that we adopt. It is best to avoid knee hyperextension during your asana practice if you are rehabilitating from a knee injury or if it feels painful to do so. Taking the knee joint into its end range of extension can make it more challenging to effectively engage the muscles around the joint therefore limiting our ability to increase strength here.

However, it might well be appropriate to choose to hyperextend the knee joint during your asana practice if you intend to stress the ligaments of the knee in order to strengthen them. Davis’ law states that by stressing connective tissue we strengthen it, while lack of use can lead to weakness and atrophy. The stress that is applied needs to be progressive. It is a good idea to explore hyperextension in a seated asana like Staff Pose (Dandasana). Attempt to lift your heels off the mat and you’ll feel your quadriceps engage and the back of your knees move towards the mat beneath you. Notice how this feels in your body.

Also, if you are attempting to get into the Guinness Book of Records for practicing the longest held Tree Pose, then you are going to have to hyperextend the knee of your standing leg to conserve muscular energy in your legs! ;-)

If you wish to avoid hyperextending your knees during your yoga practice you can do so by learning how to cocontract your leg muscles - simultaneously engaging both the hamstrings and the quadriceps. In short tutorial below, taken from my 30-Hour Yoga Anatomy Online Course, we explore the how to cocontract the leg muscles in both a seated and standing position.

It’s fine to use the cue “Micro-bend your knees,” but avoid adding that this is to protect the knee joint because in most cases that is untrue and adds to the harmful and incorrect narrative that our knees are fragile.

References:

Gray, H., Standring, S., Ellis, H. and Berkovitz, B. (2005) Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice 39th edition. New York: Elsevier Churchill Livingtone, 2005.

Loudon, J., Goist, H. and Loudon K. (1998) ‘Genu Recurvatum Syndrome.’ Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 27, 5, 361–367.

Morgan, P., LaPrade, R., Wentorf, F., Cook, J. and Bianco, A. (2010) ‘The role of the oblique popliteal ligament and other structures in preventing knee hyperextension.’ Am J Sports Med 38, 550-557.