It’s not uncommon for students to feel strong sensations in the region of their sacroiliac (SI) joints but does this mean that yoga can create instability in this area? Firstly, let’s look at the anatomy of this area.

The two hip bones join with the sacrum and the coccyx to form the bowl-shaped pelvis (Latin for ‘basin’). The bones of the pelvis are strongly united to each other to form a largely immobile, weight-bearing structure. The pelvis is the area where the lower limbs attach to the axial skeleton through the SI joints and therefore plays important roles in movement. The bony pelvis comes together to provide support for the pelvic muscles and connective tissues, which, in turn, provide attachments and support for the pelvic organs.

The sacrum (Latin for sacred) is a large triangular bone originating from separate vertebra that fuse along with the intervening intervertebral discs. One of the functions of the sacrum is to transmit the weight of the body to the hip bones.

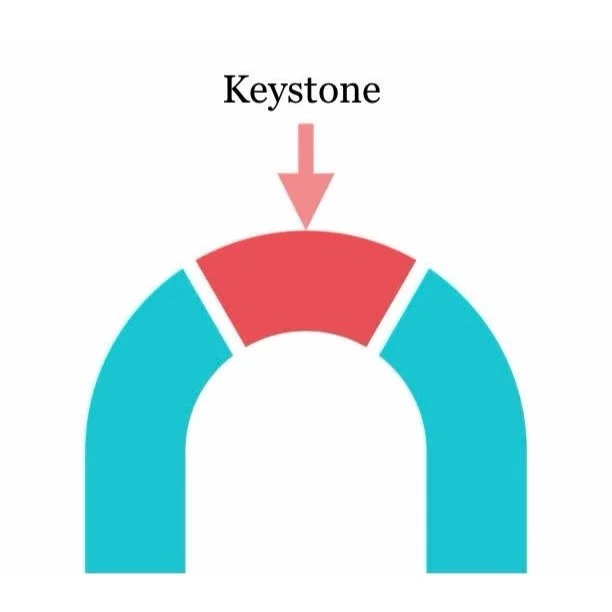

The SI joint is the largest axial joint in the body and is formed by the crescent-shaped articulation between the medial surface of the ilium (part of the hip bone) and the lateral surface of the sacrum. Part of the joint is fibrous (immoveable) while part is synovial (freely moveable). The SI joints are designed primarily for stability. Their functions include the transmission and dissipation of loads from the axial spine into the lower limbs and facilitating childbirth. The interlocking symmetrical grooves and ridges of the SI joint articular surfaces contribute to the highest amount of friction of any moveable joint in the human body. The keystone-like bony anatomy of the sacrum further contributes to stability within the pelvic ring. The sacrum is wider superiorly than inferiorly and also wider anteriorly than posteriorly, permitting the sacrum to become ‘wedged’ into the ilia within the pelvic ring. These properties are believed to enhance the stability of the joint against shearing from vertical compression (e.g. gravity) and anteriorly directed forces on the spine (Vleeming et al 2012).

SI joint stability is also provided by the strongest ligament system in the body. All of these ligaments help to support and immobilize the sacrum as it carries the weight of the body. The SI joint is additionally supported by a network of muscles that help to deliver regional muscular forces to the pelvic bones. Some of these muscles, such as the gluteus maximus, piriformis, biceps femoris and the lower lumbar multifidi and erector spinae, are functionally connected to SI joint ligaments.

The SI joint rotates about all three axes, although the movements are very small and difficult to measure. In a study by Egund et al (1978) the authors found the maximal rotations and translations of the SI joints in their subjects to be 2.0° and 2.0 mm, respectively. A larger study by Jacob and Kissling (1995) found similarly small limits on rotation (1.7°) and translation (0.7 mm). Kibsgård et al (2014) report that movement in the SI joint during a single-leg stance is small and almost undetectable.

Pain often tells us that there is a problem that needs to be addressed, but it rarely tells us what the problem is, where it is, or how bad it is. I had a student who would experience pain in this region every time they felt stressed. Does this mean that the pain was “all in their head”? No. It means that psychosocial factors can influence the development of persistent pain conditions. Pain in the region of the SI joints doesn’t necessarily mean that there is an issue here

Fear-based beliefs set people up with negative expectations, which has been linked to poorer outcomes and greater pain (Bialosky et al 2010). Fear-avoidance beliefs have been shown to be prognostic for poor outcome in patients with lower back pain (Wertli et al 2014).

The SI joint is STABLE by nature and it’s unlikely that a yoga practice will lead to instability. We don’t have to use cues such as “engage the pelvic floor to protect the SI joints”.

Here are some top practice tips for anyone who is experiencing SI joint pain:

Allow the pelvis to subtly turn in the direction of the main force, e.g. in Revolved Chair pose it’s okay for the opposite knee to move forward slightly.

In supine twists it can often feel better to find a comfortable position for the pelvis and then move the upper body rather than the other way around.

Focus more on mobility than flexibility – play with your *active* range of movement and avoid using external force in twists, e.g. using the opposite arm as a lever.

This 3D animation, taken from my 30-hour yoga anatomy online course, explores the anatomy of the pelvis, including the SI joints: https://youtu.be/tHoAjryqZyI

References:

Bialosky, J., Bishop, M. and Cleland, J. (2010) ‘Individual Expectation: An Overlooked, but Pertinent, Factor in the Treatment of Individuals Experiencing Musculoskeletal Pain.’ Physical Therapy 90, 9, 1345–1355.

Egund, N., Olsson, T., Schmid, H. and Selvik, G. (1978) ‘Movements in the sacroiliac joints demonstrated with roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis.’ Acta Radiol Diagn 19, 833–45.

Jacob, H. and Kissling, R. (1995) ‘The mobility of the sacroiliac joints in healthy volunteers between 20 and 50 years of age.’ Clin Biomech 10, 352–61.

Kibsgårda, T., Røisea, O., Sturesson, B., Röhrl, S. and Stuge, B. (2014) ‘Radiosteriometric analysis of movement in the sacroiliac joint during a single-leg stance in patients with long-lasting pelvic girdle pain.’ Clinical Biomechanics 29, 4, 406-411.

Vleeming, A., Schuenke, M., Masi, A., Carreiro, J., Danneels, L. and Willard, F. (2012) ‘The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications.’ J Anat 221, 537-567.

Wertli, M., Rasmussen-Barr, E., Weiser, S., Bachmann, L. and Brunner, F. (2014) ‘The role of fear avoidance beliefs as a prognostic factor for outcome in patients with nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review.’ Spine 14, 5, 816-36.